Five tips for integrating feedback on your work.

So someone told you some stuff about your work and now you have feels; vulnerable baby Chelsea writer stories for your enjoyment; practicing resilience mindset.

Hi everyone,

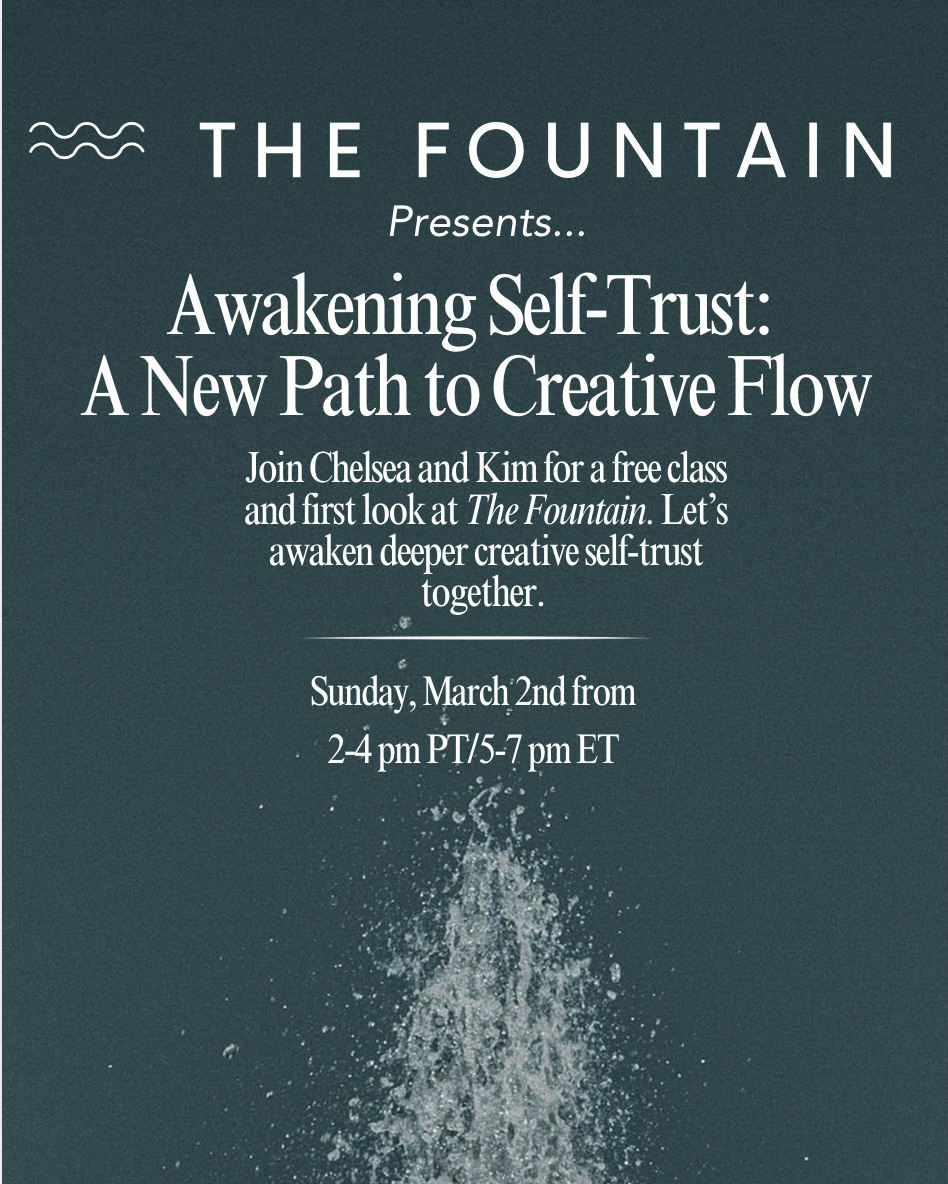

Before we dive in I want to let you know that in celebration of launching The Fountain (follow us on insta!) in March, Kim and I are hosting a FREE class on self-trust and creative flow, and offering a first look at our new membership-based platform. I so hope you can come. Register HERE now!

Okay, onto our scheduled programming. :)

I recently listened to this episode of Diary of a CEO where the president of Shopify, Harley Finkelstein, talks about what he looks for in people he wants to work with and invest in. It really resonated with me. Put simply, he said that when a wave comes, there are people who will run to the shore, grab their towels and head home, and then there are people who grab their surfboards.

Now, I recognize that these sort of inspirational lines can sometimes fail to recognize nuance—surely there’s a good reason someone would run to the shore and it doesn’t make them bad—but also, there’s a way that a line like this works for me. It’s simple, demonstrative, and strikes quickly. And often that’s what we need to take a small action and another small action and another…

I learned this growing up in AA with all the one liners. (Some of my earliest memories are crawling under the chairs of meetings, sorry mom!) Lines like these are divisive, especially among intellectuals, because they prompt a choice: you can choose to be cynical and pick them apart until they die (how’s that working for you?) or you can choose to quickly implement them and abandon doubt in service to the greater goal.

Phrases like one day at a time, do the next right thing, progress not perfection, keep coming back, it works if you work it, show up for your life, etc, still bounce around in my head and serve as little cues to get back on track in my head. They work because they coax the brain to build those new neural pathways toward new thought patterns. They stand in the face of your well worn bullshit with a stop sign.

So Finklestein is saying is that he wants to work with people who have the resilience to ride the waves, and instead of abandoning the scene at a hint of challenge, they will grab a tool that will enable them to find a way to stay in it.

The image of the surfboard makes sense to me and I agree that this resilience is a superpower and something all writers can use. There are plenty of reasons a person might feel distanced from their resilience if their trauma is not processed/healed/acknowledged, but assume that you have done enough of that work, that you can access that resilience in yourself and actually build on it. That you can take things that are challenging and move through them not by denying them, but by staying with the wave of the feeling on your surfboard rather than watching from the shore.

I tell this little story in service of the topic I want to discuss today which I believe is connected to resilience.

If you’re reading this it’s somewhat likely you’ve sat in the workshop chair before and listened as a group talked about their experience with your work. Perhaps you like me, grew up in the classic workshop model where the writer in question stayed silent while the group had their discourse, and maybe the writer asked a question or two at the very end. My MFA workshop was based on this model if you’re curious. Maybe you’ve never been in a workshop but had a writing group, or joined a class where feedback was part of the deal. As a teacher, I’ve taught many ‘classic’ workshops because it’s what I knew. Personally, when I went to my MFA, I wanted people to be tough on me because I wanted to get better. I knew the only way I would is if I approached each day with a beginner’s mind, which was convenient, because I was in fact a beginner.

I’ve been out of the classic workshop model for awhile now. I think the last one I taught was a chat-based class for Catapult in 2019 or something, and I seem to remember organizing it the same way—giving group space to talk about the piece at hand while the writer observed and took notes, silent. At the end, I always gave the writer a chance to ask questions. I don’t know if this model is used as much now. Maybe it is, maybe not, I really just don’t know, but I know in my own writing group, we use a form of it. That’s because we want to know what the group has to say on their own, before the writer has a chance to do their explaining. I know for me, I don’t want to interrupt them until they are done and it’s my turn to ask questions. The reason for this might be obvious, but it’s because it’s valuable for me to know what someone’s experience was like in their read. This works in my case for a few reasons:

My group is vetted. This is a 4 person group that has known each other a long long time, has read every single work we’ve ever written, and was put together for the express reason that we trust and love each other. So you can see how this differs from an MFA program or random class. By nature of a group like this, our feedback is already tailored to be respectful, smart, generous, encouraging, honest, and intuitive. Intuitive in the sense of knowing when to push and knowing when the person mainly just needs the nod to keep going.

For me, in this environment, it’s helpful to hear what everyone thinks and my brain files things right away into information I will use, information I will consider, and information that doesn’t sound right to my inner knowing. There’s also a category for information I’m avoiding and that I especially need to listen to ;)

But let’s track back a bit to my MFA experience. Here’s a room of perfectly nice people, but it’s a larger group and we don’t know each other intimately. At the helm is a teacher we all respect. And what gets said in that room is all over the map in terms of taste, temperament, and style. I always felt thrilled to hear what all those people had to say, the harshness and the complimentary. I think especially at that time, just to be in that room at all seemed like a supreme honor, that all those people had turned their attention to my words in such a focused way. Remember that attention like this can be a form of love. But I hadn’t always known how to sit there and receive. The truth is most of us learn how to do it in the moment if we ever do because last I checked these programs don’t really take the psychology of the experience into account. I digress.

When I was eighteen I took a community college creative writing class that was a workshop style. We turned in short stories and I’m not sure what I expected when it was my turn, but I didn’t like what was happening. The teacher had many suggestions, none of which I remember now, though I’m sure they were all in the range of normal. But they slayed me. My face burned as I sat in that room and everyone talked about me as if I wasn’t there. At the end, he turned to me and asked if I had any questions, and I said, “Well, I guess you didn’t like the story very much.”

Of everything said that day, that’s all I remember verbatim because I was boiling in an uncomfortable stew of defensive rage—I had never felt so misunderstood! I wanted to correct the things that were being said.

“Well, I guess you didn’t like the story very much,” came from my mouth. Oooof. I’m glad I didn’t stop writing after that.

I look back at that girl in the chair and feel compassion. It’s good I have that memory because it locates me in the mind of someone who has never been put through that particular machine and gives me sensitivity toward them. However, I’m so glad I got over it and kept surfing.

By the time I was in graduate school for writing, I wasn’t there for compliments, though they were bolstering when they happened. But because the focus really was on how to make a story stronger, more true (meaning, sense, clarity!) receiving a compliment was a true treat, and because it was on the rarer side, I trusted it and it motivated me.

But here is the point I want to really drive home: While I was all ears for what my cohort had to say, I knew somewhere deep down, that I still knew best. That all feedback, no matter how perfect and wise it is, is only a prompt.

Let’s unpack what I mean here.

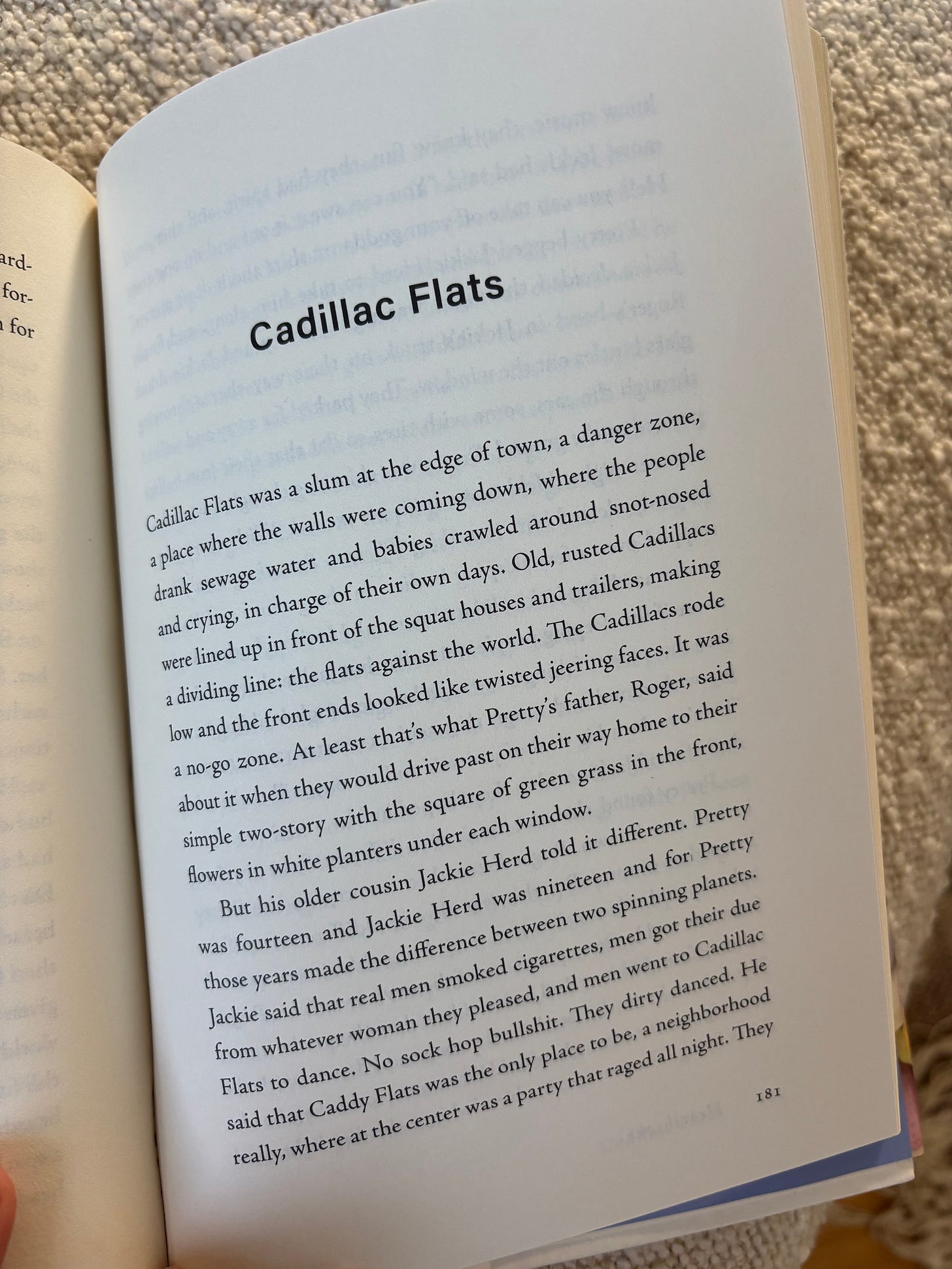

I remember a specific day in workshop toward the end of my program where I’d turned in the story Cadillac Flats (one of two stories I workshopped in my MFA that wound up in Heartbroke for the curious!). Cadillac Flats is a challenging story—one that deals with generational trauma, a gay teenage son trying to conceal his true self from his WWII veteran father, racial tensions in a small town, familial violence, first love, coming of age, friendship, etc. There’s a scene where the father shoots a gun off in the bathroom, etc. It was loosely inspired by a place my father had told me about from his childhood and was in some ways my attempt at understanding him.

The group didn’t like how dark it was. They felt that I should pick like, one traumatic thing and stick to it. I believe the phrase used was “piling on tragedy.” You know how an idea picks up steam in a group, where once one person opens the door to a way of thinking, anyone else who somewhat thought that same thing is now fullbore on that team? Well that happened, and basically everyone in the room but maybe one or two people seemed to agree that my issue as a writer in this case was that I needed to lighten up a little.

I heard them out and took my notes, all the while knowing that while they were right on some level, they were also wrong.

What they they were hitting on was true—there was a lot of bad shit happening in the story. But the answer for me as an artist then and now, wasn’t to minimize this impulse or change something. Sure, I could have made this boy’s life a little easier, or taken one hard thing off his plate (did the mom also have to be so sad???)…but there was something about that that felt like the easy way out. That’s because it was the easy way out. The comments didn’t resonate with me, because my particular artistic path and the reason I was driven to write in the first place, is that I need to make sense of a life that had that many bad things happening in it at once.

Why? Because those were the lives I knew the best. Those were the lives of my family and the people I’d watched growing up. It was what interested me, the absolute pile on of life. I knew good fiction could carry it the way I needed to tell it and I knew that from reading. Denis Johnson, Dorothy Allison, and Toni Morrison’s work was the work I idolized, and I didn’t seem to see them making their characters lives easier. The contrary. If anything, by reading them, I was learning that writing trauma in all its complexity, all its great pile on, was not only possible, but was vital. But what the workshop was getting at was capital T true: I just wasn’t doing it well enough yet.

After the MFA, I knew my work would be to build fiction machines that could carry the load of all I wanted to say and that my specific assignment was that I was not to back down on this because if I did, I’d abandon myself in the process. But I would have to get better at writing, I’d have to sharpen my senses if I wanted to do it my way.

(And remember, the only real way is your way. If you try to please people in your creative work there is a sort of death that occurs. Had I walked away ashamed and resolved to write a quieter sort of tale, then I might as well have just stopped right then and there.)

The great part though is that you will never do something everyone loves or even likes. I mean, think of your favorite work of fiction and go look up its one star reviews—of which there will be plenty! Someone will hate on a thing for the very reasons you love it. Does that diminish your love for it? I really hope not.

But you have to stick by yourself and finely attune yourself in those environments when it might be easy to give the authority over to a group or a teacher or an editor or an agent. No one knows the answers but you. People have great ideas, they have suggestions, and what I love about the editorial process is that someone might offer you a crystal clear solution to a problem in the work, and it may ring true for you, and you take it, and great! Or they may offer a direction that you know right away isn’t the right thing but it sparks the right thing. Or it makes you ask a question and in that question a new thought arises. In this way, feedback becomes a prompt. All of it, a prompt.

As part of my puzzle of hustles, I have taken freelance book length editing clients on since around 2020. I often have very prescriptive ideas for solutions. That’s how my brain works. My editing process is that I read a book and sort of get a big picture download into my brain about what needs to happen. I feel into this very intuitively. It’s fun because I love figuring out plot stuff and can usually sense when a short cut was taken, and can also sense where that writer shied away from the tough stuff. And while I offer prescriptive feedback, I really explain that is it only a prompt. A springboard for what the real path might be.

Because in a healthy working system: as soon I say I idea, the writer, understanding I am not god, immediately has a reaction. The reaction is telling. If we can get past defensiveness and into resilience, usually that’s where the real solution lies. If the writer is preoccupied with defending their choices, then not much can get done. But if they are open to hearing, and then using what I say to measure their response—Do I agree? Does that seem true to my story? I like the idea of having the character do something different here, but Chelsea’s idea is insane, so what if I tried this instead….That’s the gold! This bouncing off of is where we get somewhere.

If a trusted reader is confused about an aspect of my work in a feedback environment, and I think I have covered that base—their confusion is a prompt for me to make damn sure I’m right, or to do it in a better way. Maybe they didn’t read close enough. That’s totally possible. Or maybe I need to be better.

Be better. I hope that’s not triggering for anyone. I know our society is so focused on optimization sometimes it feels like a kettle going off non-stop. But if you have decided being a writer and sharing your work is what you want to do with your life, you owe it to your story to be as good as you can be, and the only way you can do that is if you are true to yourself in the process of revision.

What’s interesting is that most of the time we already know what’s going wrong. The best feedback points us in that direction and clears the path to make adjustments. I tend to advise my clients that more feedback is not better. What you need is trusted feedback. I don’t really understand the idea of beta readers in huge batches. How could that not be crazy making? And what makes you think those people know what they’re talking about? My sense is that mass feedback in this way could be destabilizing and create an impossible environment where you try to appease too many voices, and by doing so lose the energy of why you even wrote the thing in the first place. (I suppose though, even in this environment one could utilize the prompt filter and be okay, maybe? Maybe?!)

I know my writing group is going to offer feedback I value because I value their work in the world and understand their sensibilities. They are aware of the target I’ve set for myself as an artist. They know the sort of writer I strive to be. Do you think there’s someone on earth who thinks Demon Copperhead was a bit much? Had too many sad parts? Piled on a bit of tragedy? Of course there is! There’s a lot actually. And this book is a HUGE success. Huge huge. But no matter how good something is to one person, there will always be someone there to say what a piece of crap it is. It’s just a fact.

So knowing this, will you please your own soul or will you try to make a mass group happy? Only one of these is possible and it’s the first one. Only one of these is worthwhile. And again, it’s the first one. Below are my tips, and I hope they are useful to you.

Make sure it’s coming from a trusted source. Is this person a reader you trust? Why do you trust them? If you are in a class environment you can’t vet everyone, so the next question is:

Be okay with challenging feedback. This means, if you find yourself in a class environment (which is great! I’m a big fan of toughening up a little bit and hearing hard stuff if only to practice using it all as a prompt) are you ready to listen, really listen to what other people are saying, and allow whatever goes down to shape your inquiry about your work rather than define it? I think it’s a growing experience for every writer to find themselves as the topic of a workshop group. You will know when this phase is over for you, and you need to move on to a more trusted circle, but having this initial experience, as long as you take it all as a prompt, is good for you generally. Grist for the mill as they say and if you let it, a great way to develop your sense of what feels right for you as a writer.

Feel all your feels and then move on. Maybe something was said that made you reactive. Remember me at 18 saying OUT LOUD, “well I guess you didn’t think the story was very good” in a haughty manner to my teacher, probably arms crossed over my chest, legs kicked out like I didn’t care. Reader, I cared so much. I wanted that man to tell me (and the class) I was a prodigy, I was the best one there! A future fiction champion in the room, everyone! But he did not. And I had to feel thru what came up which was that I was triggered AF because I longed for maternal love and approval and I was not gonna get it in that fiction workshop, lol. But I had to feel those feelings, and it was actually okay that they came up because I am human and you are too. It’s okay to feel defensive, and sad, and annoyed, and overwhelmed after receiving feedback on your work. You. are. human. But the important thing is that once you shake that off, you use all that feedback as a prompt. Oh, someone thought that brother character was thinly drawn? Okay, go back and take a look. Maybe the answer isn’t to bring him out more, maybe he needs to actually retreat because he’s not central to you and your vision. So in this example, you do the opposite of what that person said, but you still arrive at a solution. Your solution. It’s always the better one.

Listen to your gut. You know when something rings true and when something doesn’t. Note it, listen to it. It’s not random! It’s information. It’s valuable. Turn the volume up on that voice. I guarantee it has revisionary thoughts for you.

Try shit out. By this I mean, as you draft, if you feel an inkling to do something that scares you, try it. Maybe it seems too weird, or tricky or you’re like, oh no what will the marketplace say!! The fact is you will never know. It changes all the time. And if you don’t scratch the itch your work will suffer and you will know it. If you try something and it’s bad, you can always take it out, and you will have learned something from doing it.

If a group or class feels bad to you, find a different one. Find people who embody the sort of writer you want to be. In AA the saying is stick with the winners. Meaning hang with the people who are serious about sobriety. Hang with the writers who display the qualities you admire. When you choose a sponsor you find someone who has what you want. Because why the hell would you want to learn and hear from someone whose work you don’t really like?? Put those mirror neurons to use for you and find people who are shining and confident and not in scarcity mindset. The feedback they will give you will come from a non-envious place and will be more true.

I could say a lot more here but I’ll end by letting you know that next month Kimberly and I will be launching The Fountain. And to kick things off we’re hosting a free class on self-trust. Sign up for the class HERE. There will be some generative writing, some self-contemplation, and a first look at our membership-based platform. The class is our gift to you and by attending you will get a link to a free Clearing (our handmade visualization tracks).

Hope to see you there and I can’t wait to tell you more about the platform. So much to say!! But for now, I leave you with the info below. Happy writing.

✨ To every creative who’s longed for a space to learn to trust their deepest artistic instincts and build an unshakable practice…✨

As writers and teachers, we’ve witnessed again and again how the greatest barrier to creativity isn’t lack of skill—it’s our relationship with ourselves. We created The Fountain because we understand that creativity flows most naturally when we reconnect with our innate artistic capabilities.

Join us for an afternoon of creative exploration where we’ll engage in a purposeful writing practice together, share our vision for sustainable creative flow, and give you an exclusive first look at The Fountain membership platform—our carefully crafted digital space for clearing the path toward your highest artistic self.

All attendees will receive a free custom Clearing (one of our special visualization tracks) and the opportunity to sign up for access to our stream of courses, Clearings library, and community ✨

This gathering launches something transformative—a place where your unique creative voice can thrive, where artistry emerges from flow rather than struggle, and where you’ll access proven tools to produce the work that only you can create.

Step into your creative potential. You’re in the right place, and it’s the right time⛲️

Sunday, March 2, 2 PM-4 PM PST/ 5 PM-7 PM ET Virtual Event

Cost to attend: our gift to you ✨⛲️🧠

Email biekerparsonsworkshop@gmail.com to secure your spot and receive the Zoom link the Friday before class. 📧

Is The Fountain a cult and if it is not, could it please be, because I would like to join it?

How did you know I needed to hear these words this week?? I’m in the middle of Tin House’s Winter Workshop and about to dive into my workshop’s critique letters feeling so, so anxious about them. Thank you so much for writing this! ✨💖